Self-portrait of the artist as a beautiful filmmaker

The films of Mia Hansen-Løve are moving, rapturous and deeply personal

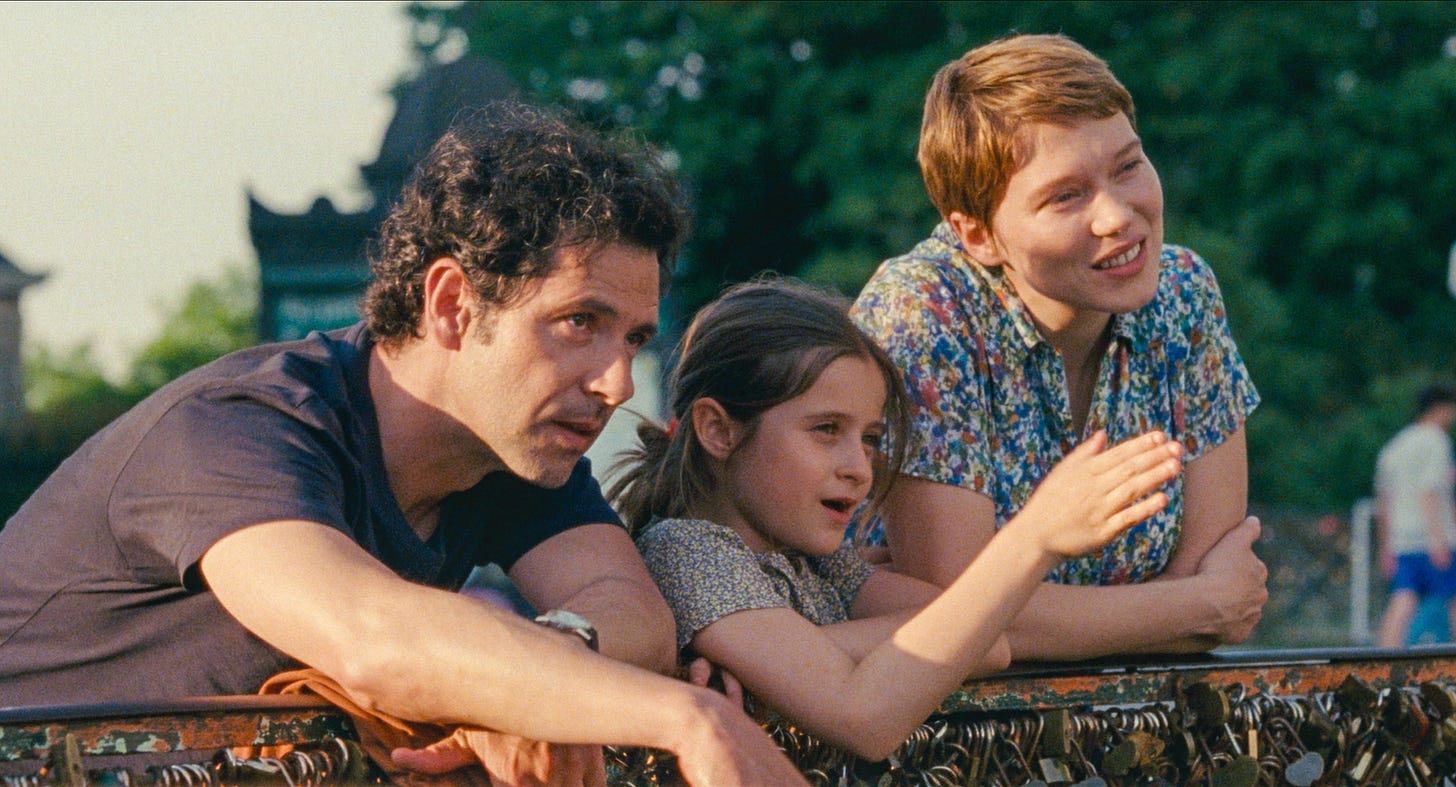

Melvil Poupaud, Camille Leban Martins and Léa Seydoux) in One Fine Morning. (Image courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics.)

A friend recently asked about my favorite films of last year. Thinking about the list in my head, I quickly realized a significant number were made by French women—Audrey Diwan’s Happening, Alice Diop’s Saint Omer, and the sharply realized One Fine Morning, by the wonderful Mia Hansen-Løve.

A standout of the last New York Film festival and now playing at art house theaters, the film is another of the filmmaker’s trenchant and absorbing stories about love, independence and the need for self-expression. Few directors have such a sharp feel for capturing melancholy, grace, or emotional vulnerability.

Her great theme is dramatizing the interior consciousness of women—the tumult of mad love, contentious family history, or the inevitable conflict about the need to belong and also assert a radical independence.

Her films have displayed a striking natural talent and a poetic, rapturous ability for capturing movement. The women are never just spectators. Each is accorded a jolting, lyrical quality, irrespective of class or social distinction: Marie-Christine Fredrich in her frank, intense debut, All is Forgiven (2007); Alice de Lencquesaing in her poised, ambitious Father of My Children (2009); Lola Créton as the beautiful, infatuated Camille caught between two very different men in her autobiographically inflected Goodbye, First Love (2012).

Her fourth film, Eden (2014), which fictionalized her brother’s experiences in the French electronic music scene, beautifully transmuted her family history into a vibrant cultural history. The movie’s central character, Paul (Félix de Givry), describes his work as divided “between euphoria and melancholia,” an apt description of the tonal range and plangent emotional currents.

(At Sundance one year, I had the pleasure of interviewing Hansen-Løve here.)

Mia Wasikowska in the interpolated film of Bergman Island. (Image courtesy of IFC Films.)

Now the director is having a wonderful one-two moment. Her previous feature, the outstanding Bergman Island (2021), is now out in a beautiful deluxe Blu-ray from Criterion.

The formal and thematic connections of her fifth feature, Things to Come (2016), Bergman Island and One Fine Morning are fascinating to ponder and think about.

Taking in these films consecutively is like getting lost in an epic novel, the parts and movements bound together in theme, mood and style, even as the characters and situations vary moment to moment.

Few directors have been so nakedly autobiographical, as a recent New York Times profile underscored.

Hansen-Løve first caught attention with a small though important part as a preternaturally sharp schoolgirl carrying out a furtive affair with a much older novelist in Olivier Assayas’s chamber drama, Late August, Early September (1998).

(The film is available to stream at Criterion Channel. It’s essential viewing).

After a smaller part in the director’s follow-up feature, Hansen-Løve shifted her attention away from criticism and cultural journalism towards making her own shorts and larger projects.

She has been enjoyably and wonderfully prolific, with films marked by an intelligence, novelistic detail and formal flair. She has a natural and wonderful rapport with her actors.

The actresses in those first three films were young and still forming. The rawness and uncertainty of the emotions produced some rapturous, spellbinding moments of self-discovery, feeling, beauty.

The protagonist of Things to Come, a university philosophy professor played by the great Isabelle Huyppert, is older and much more professionally established. That proved a crucial transitional work.

In Bergman Island, the great Vicky Krieps plays a filmmaker who travels with her partner (Tim Roth) to the island of Faro, where Ingmar Bergman lived, worked and made many of his signature works in the sixties and early seventies.

The movie sharply punctuates an artist’s fractious life, uncertainty, confusion, with a probing, glancing intelligence. Hansen-Løve is fantastic at capturing something particularly difficult to dramatize, the act of creativity. (The movie, I found out at the New York Film festival the year it played there, had a very complex production history. It’s incredible how seamless the movie is.)

In reckoning with the legacy and meaning of Bergman on her life and work and eager to establish an artistic identity separate from her better known partner, Vicky ostensibly dreams into existence the autobiographical script that has consumed and torn her apart. (The resulting movie, “The White Dress,” of which we see a fragment, has clear affinities with Goodbye, First Love.)

Structurally the first four films are marked by their two- or three-part formats. Time is always elastic and malleable in her work. The early films of Hansen-Løve were primarily shot by Stephane Fontaine. Starting with Things to Come, the director began a professional and artistic relationship with Denis Leonor—an important collaborator of Assayas who shot Late August, Early September.

Lenoir favors the fractured and elliptical. In Bergman Island and One Fine Morning, the light is radiant. The camera is never passive; it moves and flows. Image and sound are naturally expressive and tethered, yielding sensations and feelings at once natural, loose, engaging.

Like Bergman Island, the new film privileges the inner world of a beautiful, accomplished professional woman. Sandra (Léa Seydoux), a widowed mother with a vivacious young daughter (Camille Leban Martins), works as a translator.

In the act of her daily routine and professional activities, at academic conferences and movingly, a special ceremony honoring the war dead from D-Day, Sandra emerges, almost imperceptibly, as a living, dynamic woman of shape and physical expressiveness.

One Fine Morning is built, beautifully, around notions of reconciliation, of the past, and suggestively, of a reclaimed sexuality. It’s not all exhilaration. Her life is marked by sadness and pain, in the visibly declining mental and emotional state of her father, Georg (Pascal Greggory). Like the Huppert character of Things to Come, her father is a distinguished professor of philosophy now ravaged by Benson’s syndrome, a neurological disorder that wrecks memory and sight.

As Sandra, with her sister, tries to map out the best medical care for her father, her already messy world is further jolted by a chance encounter with Clément (Melvil Poupaud), a cosmo-chemist and former colleague of her late husband.

Their natural ease and rapport (with some hints of deep attraction) leads to something much more primal and direct, a sexual rejuvenation that opens up new emotional outlets for Sandra.

“I just feel like my love life is behind me,” she says. That rebirth is sensual, beautiful and deeply elemental.

“I’ve forgotten how,” she says.

“You can’t forget.”

Life is rapturous, confusing, wistful. It is rarely linear or easy. The fact that Clément has a wife and child adds to the natural complexities and contradictions of daily life.

Like virtually all of the characters of the director’s films, Sandra is caught between worlds, negotiating fluid and unstable situations and actions. However reckless, self-involved or confusing the choices, the conviction or depth or underlying feelings are never really in doubt.

Just as Camille oscillates between two very different men in Goodbye, First Love, Sandra moves between her lover and father. She is never secondary in any of the emotional dynamics. She is deeply present, with a solidity and steely toughness.

Like Krieps, Léa Seydoux is a marvel—resourceful, complex and highly versatile. Her Sandra is tender, vibrant, emotional, and deeply whole. She withholds or sometimes rushes in, without blinders or reserve. She charges through, nervy and unpredictable.

Pascal Greggory is also one of the great actors of French cinema, with a body of work, and a collaboration with some of the all-time greats (Assayas, Eric Rohmer, Raul Ruiz, Jacques Doillon). During one luminous sequence, we hear his voice on the soundtrack, a fragment from a memoir he never completed. It’s an extraordinary moment.

During one tense moment between the lovers, Sandra talks about the need for distance. Autobiographical art is hard. Sometimes it’s just too personal.

The art of Mia Hansen-Løve is never self-flattering or uncritical. Her work speaks to something essential and necessary, confirming our never ending desire to continually break free and find our own way.

Vicky Krieps as the restless and gifted filmmaker in Bergman Island. (Image courtesy of IFC Films.)