Images, or the man in the gray suit

On movie modernism, adaptation, and coming to terms with a great director's work of dread and cultural occupation

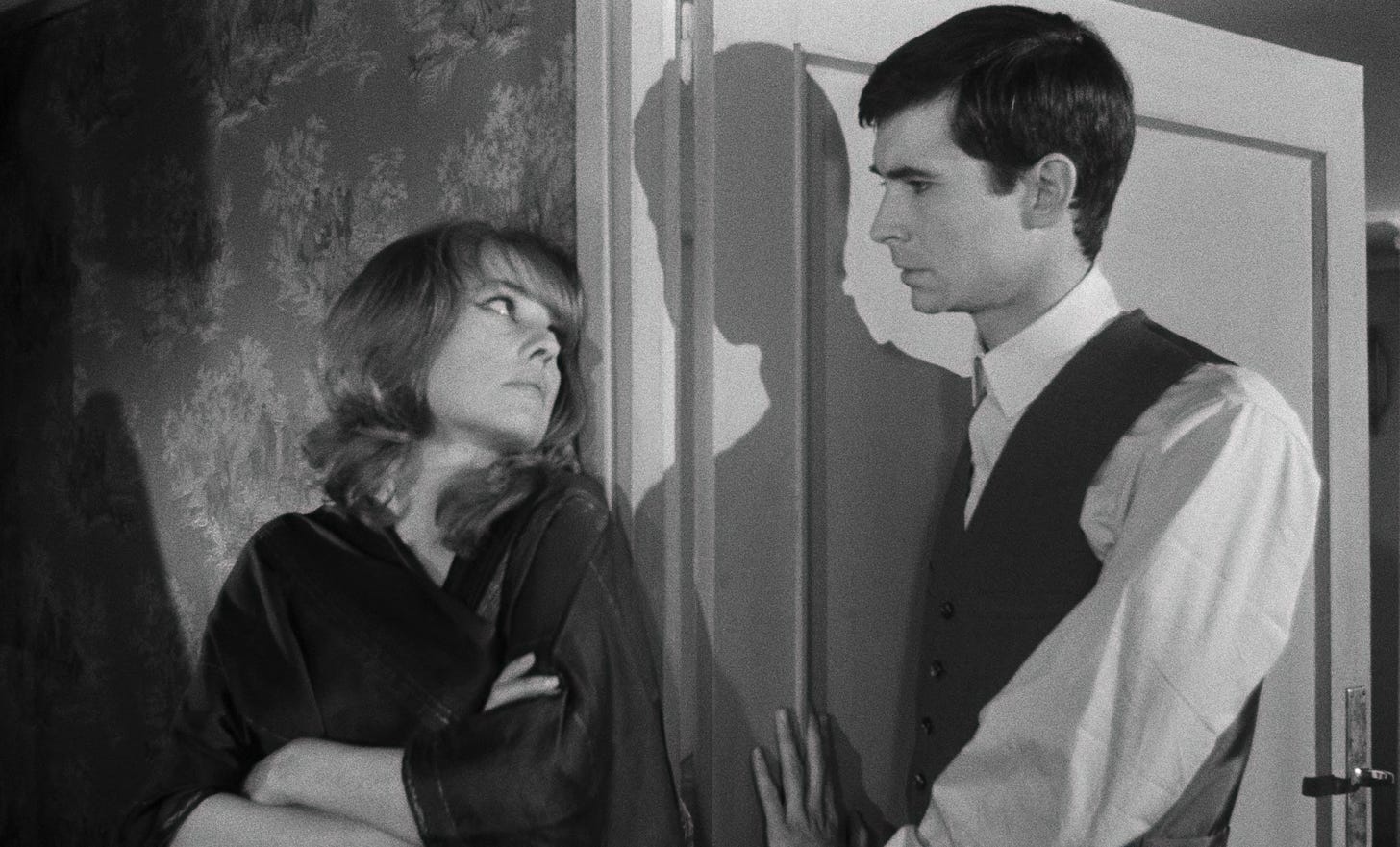

Jeanne Moreau and Anthony Perkins, in Orson Welles’ The Trial, adapted from the Franz Kafka 1925 novel. (All film stills courtesy of Criterion).

“Welles has the approach of a popular artist: he glories in both verbal and visual rhetoric. Movies gave him the world for a stage, and his is not the art that conceals art, but the showman’s delight in the flourishes with which he pulls the rabbit from the hat. (This is why he was the wrong director of The Trial, where the poetry needed to be overhead.)”

—Pauline Kael

“The Trial deserves a derisory footnote all its own, but with reservations. Since everything Welles has done since Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons has been denounced as a betrayal of his talent, it is possible to sympathize with his decision to hurl Kafka at the culture-mongers. The final irony of this most absurd situation is The Trial is the most hateful, the most repellant, and the most perverted film Welles ever made.”

—Andrew Sarris

I’m paraphrasing, but the great French director Olivier Assayas once told me he’d rather see a flawed or failed work by a director he admires rather than a successful film by a filmmaker he didn’t much care about.

My standards are naturally higher for the directors who hold a great personal or artistic meaning. At the top of my personal pantheon is Orson Welles—the artist I regard as the most important figure in postwar American cinema.

Does that make him a greater director than Ford, Hitchcock or Renoir? Probably not, given those directors’ greater body of work, consistency and depth. It hardly seems necessary or valid to downgrade Welles because he made fewer completed films.

As the magisterial example for The Other Side of the Wind proved, Welles was indefatigable, relentless, tireless, until his last breath. The feel, look, design, compositional and flair of a Welles film is unlike any other director.

It is the most telling, graceful and probing example of his art that even in the most tragic, misbegotten or ridiculous examples of others tampering with and mangling his art, the greatness with Welles endures.

Even the mismatched cuts and screwed up tempo and rhythm of The Magnificent Ambersons, Touch of Evil and Mr. Arkadin retains their power, beauty, poetry and wonder.

We react angrily to the imperfections, at the ghastly, hard touch imposed by others, but the beauty, power of the original author, his presence, his authority, his sensibility, is too great, resourceful and overwhelming to fully eradicate or destroy. The genius is unmistakable, unalterable.

Does that make every Welles film indisputably great? Or thinking about it another way, what do we make of the films that are not at his highest level of accomplishment?

I’m speaking specifically of The Stranger (1946), Macbeth (1948), and The Trial (1962), visually deft, formally interesting (especially the interplay of image and sound) movies that also seem slightly mannered, never quite there, or as the great writer and Welles scholar James Naremore said of The Trial, “divided against itself.”

A big part of the problem of the minor or lesser Welles’ films, I think, is partly generational, and how you originally experienced them. Welles’ adaptation of Franz Kafka’s The Trial seemed the most glaring example of this compromised, or diminished viewing experience.

“Given the impact of screen size on what he’s doing, you can’t claim to have seen this if you’ve watched it only on video,” Welles’ scholar Jonathan Rosenbaum pointedly remarked of The Trial.

That certainly spoke to my first encounters with The Trial.

Director and writer Orson Welles, who plays the advocate, in The Trial.

If memory serves, my earliest viewings were exactly degraded video or faded prints. In the example of all the major Welles films (Kane, Ambersons, The Lady from Shanghai, Touch of Evil, Chimes at Midnight), I always felt plugged in, immersed and deeply engaged, the patterns and shapes accruing in depth, feeling and emotional intensity.

With The Trial, I always felt as alienated and disassociated as Kafka’s Josef K., detached and feeling as though I were locked out and watching something from the outside. It was creepy, strange, and peculiar. My own feelings about the film were always unfinished, amorphous, unresolved.

I was eager to find the right time and moment to come up with some answers.

A couple of years ago StudioCanal and Cinematheque francaise (with underwriting from Chanel) put together a gorgeous 4K restoration of the original 35mm camera and soundtrack negatives at L’Image Retrouvee in Paris.

About a year ago I saw a press screening at the Music Box Theatre in Chicago of that 4K restoration. (Right after, I made a point of reading the novel again, the widely regarded Breon Mitchell translation.)

Recently Criterion published a 4K edition, and I’ve been watching the film a couple of times.

The most important supplement to the Criterion presentation is the legendary talk Welles gave at the film auditorium of University of Southern California on November 14, 1981, that was shot by his cameraman, Gary Graver.

The unfinished film, called, Filming The Trial, was another of the director’s idiosyncratic essay films, originally intended, I believe, as a companion work to Filming Othello. As a Wellesian, it was deeply satisfying to finally see the material.

As I have said before, it is never out of time or fashion to think about and wonder about the art of Orson Welles.

Compared with Welles’ other films as a European independent, one of the most striking differences of The Trial is how relatively lucid and self-contained much of the material is.

The dominant stylistic and formal energy of the other films is the instability of the image, coloring and shaping the flow, tempo and dazzling rhythms, underscoring those films’ themes of breakdown and disorder.

Peter Bogdanovich: “I told you I liked [The Trial] better the second time I saw it.”

Orson Welles: “See it a third time!”

That exchange comes from their book-length interview, This is Orson Welles.

“What made it possible for me to make the picture,” Welles said to Bogdanovich, “is that I’ve had recurring nightmares of guilt all of my life: I’m in prison and I don’t know why—going to be tried and I don’t know why.

“It’s very personal for me. [I]t’s the most autobiographical movie that I’ve ever made, the only one that’s really close to me.”

In Welles’ version, he combined characters and reordered the scenes, most significantly the rule of the guard parable, visualized beautifully and hauntingly, in the “pinwheel,” style of a husband and wife Russian avant-gardists, that opens the film.

In Kafka, that scene takes place near the end. In his voice, Welles says the story we are about to see has the “logic of a dream,” of “a nightmare.”

In talking further with Bogdanovich, Welles said: “The magical part of dreaming is what I was looking for, trying to achieve. Because dreams do have something to do with magic, and I believe in magic as the main source of poetry.

“We create entire worlds in our dreams—full of people we’ve never seen, places we’ve never been to—that seem to echo and reverberate with worlds and memories that we’ve never experienced.”

I think visually and formally, the most exciting part of the film is the labyrinth—a blank, impotence, death—the inescapable specter of falling, entrapment, trapped in space, rushing from one door to the next, with its attendant feelings of loss, and constantly plunging into the void.

Welles’ conception of Josef K., played in his film by Anthony Perkins, provides some very interesting insights into his work with actors. Perkins, Welles told the USC audience, played the “character that I saw as K., and paid the price, because nobody else sees it that way.

“I find in the book repeated indications that K. is a pusher, on his way up the bureaucracy, not Mr. Zero in the adding machine, not little Mr. Nobody, not the poor little faceless accountant, but a young man very anxious to get ahead in this awful world, and doing his best to do that, and therefore in a state of real neurosis, because he is both terrified of, and anxious to conquer, the same thing.”

If the overpowering carnal and erotic presence of Janet Leigh in Touch of Evil anticipates in thrilling and audacious ways Psycho, the casting of Perkins doubles and deepens the connections between the films.

At just past 6 one morning, K. is awakened by authorities, and told he is being arrested, on unspecified charges. The nature of the claims is almost certainly sexual, of transgression and violation, sharply demonstrated during an absurdist and anarchic early exchange between K. and the authorities, in the the substituting of “pornograph,” for phonograph, or a hilariously twisted back and forth argument about, “ovular.”

The early visual tension in the contrasts of bodies and space, of restriction and enclosure, is sharply contrasted in Perkins’ height and length, the top of his head nearly touching the low hanging ceiling.

The intermingling of the sacred and profane is a Welles’ trademark.

The sexual destabilization, in both Kafka and Welles, takes different forms and permutations, most feverishly in the three luscious and dazzling female temptresses that float and whirl around K: Miss Bürstner (Jeanne Moreau), the chanteuse/prostitute who lives in the next room; Hilda (Elsa Martinelli), the wife of the courtroom guard; Leni (Romy Schneider), the nurse and lover of his lawyer, the advocate Hastler (Welles, who originally sought out but was turned down by Jackie Gleason for the role).

The burlesque between Moreau and Perkins at the start is one of the highlights, with the slinky outfit sliding down her bare arm as he steals a kiss. (Her absence is deeply and negatively felt throughout the balance of the film.)

“Welles without his demons would not be Orson Welles, and Citizen Kane would be just another newspaper movie. It may be maddening that Welles doesn’t produce more, but it’s not a simple case of a great talent gone to waste—it’s a case of a talent that nurtures itself on waste, that thrives on disaster. Failure, frustration, impotence, irrelevance—these are the subjects of Welles’s films, and, to judge from the public outline of his career, these are the subjects he has learned a lot about.”

—Dave Kehr

Like all of his European projects, Welles encountered serious financial duress throughout the production. He was forced to scuttle his original plans of shooting in Prague and Zagreb on specially designed sets.

The exteriors were shot in Zagreb and Rome, and the interiors were shot at the abandoned train station of Gare d'Orsay, in Paris.

The Trial is a deep lament for what might have been. In Touch of Evil or Chimes at Midnight, every shot, every cut, has a force, power, vitality that burns up the screen. It’s more scattershot and flattened here, bursts of energy that dazzle and float fleetingly and then collide with larger scenes or moments that never quite congeal or take hold in the consciousness.

Taking Welles’ own admonition to watch it a third time, I think its greatest value is political and cultural. At the start, when K. is notified of charges being brought against him, he encounters three functionaries from his office. Started to see them, he angrily asks, “Are you informers?”

Welles circumvented his own blacklisting by going to Europe, like Joseph Losey or his former associate Cy Enfield. In one of the most exhilarating parts of his USC talk, he talked about being up to the challenge of adapting Kafka.

“In my reading of the book—and my reading is probably more wrong than a lot of people’s—I see the monstrous bureaucracy which is the villain of the piece as not only Kafka’s clairvoyant view of the future, but his racial and cultural background of being occupied by the Austro-Hungarian Empire.”

Franz Kafka died in 1925. His three sisters were killed in the death camps. Others have no doubt made the similar point, but John Updike was the first writer I remember forcefully binding Kafka’s alienation and existential despair to being a Jew, even a socially mobile, educated and upper middle-class.

Welles’ The Trial is unmistakably a Holocaust film, in the most visually harrowing sequence, a long pan in the flattened out landscape of a group of men, half-naked and brutalized, to the arbitrary and perverse meting out of justice that K. encounters during the tribunal.

Near the end, the two executions dress and look like Gestapo agents. “Do you expect me to do this myself,” he screams after he is handed the knife.

Welles’ ending is not Kafka. It’s nihilistic and bleak. In a 1962 interview, Welles said the original was not possible morally or intellectually. “To me it is a ‘ballet’ written by a Jewish intellectual before the advent of Hitler. Kafka wouldn’t have put that after the death of six million Jews. It all seems very much pre-Auschwitz to me. I don’t mean that my ending was a particularly good one, but it was the only possible solution.”

Asked at USC, Welles said: “I’m not Jewish. We are all Jewish since the Holocaust.”

Welles dubbed a couple of the other actors. The most distracting is the example of the great French actor Michael Lonsdale, who plays the priest. Lonsdale spoke perfect English, so I’m not sure why Welles felt the need.

More profoundly, the voice is heard at the end, with the spoken credits: “I played the advocate, and wrote and directed the film. My name is Orson Welles.”

I never get tired of hearing that.