Conversations with Paul Hirsch

The Oscar-winning editor talks about his work on Brian De Palma's greatest film, Blow Out, newly available in a stunning 4K edition from the Criterion Collection.

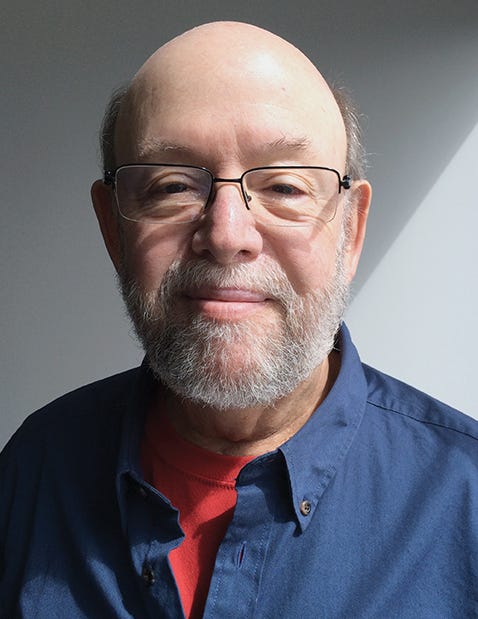

Nancy Allen, as Sally, in Brian De Palma’s Blow Out. (Film images courtesy of the Criterion Collection.)

A couple of years ago, I interviewed the editor Paul Hirsch, upon the publication of his wonderful memoir, A Long Time Ago in a Cutting Room, Far, Far Away (Chicago Review Press).

Born in New York, he spent his youth in Paris. (French was ostensibly his first language.) Hirsch has cut more than forty features.

In his varied and remarkable career, he has had a direct hand in some of the most iconic actions of popular American cinema— the prom massacre of Carrie (1976), the jump to hyperdrive in Star Wars (1977), and the break-in at the CIA vault in Mission: Impossible (1996).

He won the Academy Award for his work on George Lucas’ pop phenomenon, Star Wars.

In the original interview, we talked about his working relationship with Brian DePalma, and the 11 films they made together.

“Brian is a genius when it comes to designing visual sequences,” Hirsch told me. “I don’t think there’s anybody else who comes close. Film directors always come up with visual sequences.

“What distinguishes Brian is he is using the medium as storytelling and not simply recording actions. His basic outlook of the point of view informs a lot of what he does.”

The film I regard as DePalma’s greatest, the political thriller Blow Out, is newly available in a stunning 4K edition from Criterion.

The movie is about a brilliant sound-effects specialist, Jack (John Travolta, never better), who becomes ensnared in a political assassination cover-up after saving the life of a young woman, Sally (Nancy Allen).

Paul has some wonderful details about Blow Out.

The original working title was Personal Effects; Antonioni’s Blow-Up (1966) was not the taking off point. DePalma was actually inspired by an idea from the sound editor of his earlier Phantom of the Paradise (1974).

“I didn’t suspect it would one day become a bigger cult hit than Antonioni’s film,” Hirsch wrote.

Paul’s book is available in a beautiful paperback and Kindle edition. I caught up with Paul recently, and we talked more specifically about his experience of working on Blow Out.

(Film editor Paul Hirsch, courtesy of the editor.)

Shadows and Dreams: How had your creative relationship with Brian DePalma evolved by the time of Blow Out, which was your seventh film together?

Paul Hirsch: It was very open, but perhaps a bit less united. The successes we had each enjoyed without the other made it easier for me to speak up, and easier for him to ignore me.

Shadows and Dreams: During that era, of 35mm, and negative cutting, did you wait until the end of principal photography before you began your work?

Paul Hirsch: No, when the company leaves a location, or wraps a set, that's all the film you're going to get for a given scene. At that point, there is no reason to wait to begin cutting.

Shadows and Dreams: In your book, you talk about your concerns, even misgivings, about parts of the script. How did DePalma react to that?

Paul Hirsch: He disagreed.

Shadows and Dreams: DePalma is such a visual stylist. How protective was he about his own scripts, Blow Out, in particular?

Paul Hirsch: Brian was very bold in his choices about how to shoot his scenes. He is unusual in that respect. I can't really speak to how he behaved towards producers and studio executives during the development process, as I wasn't around.

Shadows and Dreams: Did DePalma ever mention if his script was the expansion of the riff in his earlier film Greetings (1968) where the guy is trying to get his girlfriend to look at the enlarged frames of the Kennedy assassination?

Paul Hirsch: No, but it's consistent, isn't it? The circumstances of JFK's death preoccupied many people in our generation. In any event, the riff in Greetings was more my brother Charles's obsession than Brian's. Charles produced and co-wrote the script.

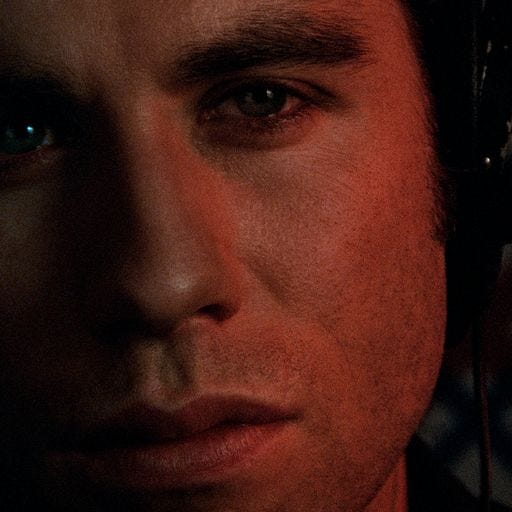

(John Travola, in his most electric performance, as the sound-effects specialist, Jack.)

Shadows and Dreams: Was the framing device of the exploitation film always the start of the film?

Paul Hirsch: I believe so. It's Brian's sense of humor.

Shadows and Dreams: The use of sound, on and off screen, is so central to the storytelling here. What kind of work went into capturing that to everybody’s satisfaction?

Paul Hirsch: Dan Sable was our sound effects editor. They hadn't invented the term sound supervisor yet. He was responsible for recording the sounds. The placement of the sounds within the scenes was critical, and I did that.

Dan moved some of the sounds, and I had him move them back. The picture cuts were triggered by the sound, and the temp effects I laid in had to be treated like dialogue, sync-wise. The picture cuts and the sounds are like in a dance with each other, and you can't shift the sound without spoiling the picture.

Shadows and Dreams: Was that your suggestion to DePalma to introduce Burke, the John Lithgow character much earlier in the film?

Paul Hirsch: I think that came out of an early screening of the film for a few friends, who found a lack of tension in the early reels. Introducing the antagonist sooner was our solution to that note.

Shadows and Dreams: Another celebrated moment, the Zapruder-influenced scene where Jack syncs his recorded sound to the published photographs. Was that an example of DePalma letting you do your own thing with the material?

Paul Hirsch: Well, he always let me do my own thing unless he had a problem with something I had done. Then we would change it.

Shadows and Dreams: Did DePalma storyboard a lot with the cinematographer, Vilmos Zsigmond? If so, did you reference any of that for your work?

Paul Hirsch: I only look at the script and dailies. Brian did his own boards for a long time, and they were difficult for me to decipher. Anyway, they are all about how he planned to shoot a scene. Once the scene is shot, they are irrelevant.

Shadows and Dreams: In your book, you talk about the conflict with you and DePalma over the final movement. How did you ultimately resolve that?

Paul Hirsch: We disagreed over the timing of Travolta's run to save Nancy Allen. I recut it according to Brian's instructions. Then George Litto, the producer, saw the cut and expressed an opinion that coincided with mine. So Brian agreed to go back to the earlier structuring, although with film, you had to take apart one version to create a new one.

So I had to try to remember what I'd done. It was all about how early or late we started John running. As for the final scene, I would have preferred a hokey happy ending, but that's just me.

Shadows and Mix: What was your reaction during the mix when you found out that thieves had absconded with four cartons of processed film, including some of the parade footage?

Paul Hirsch: Horror. Shock. Disbelief. One of the tenets of the business is you never ship anything over a weekend. It makes it too easy to lose. But the studio had done just that with our negative.

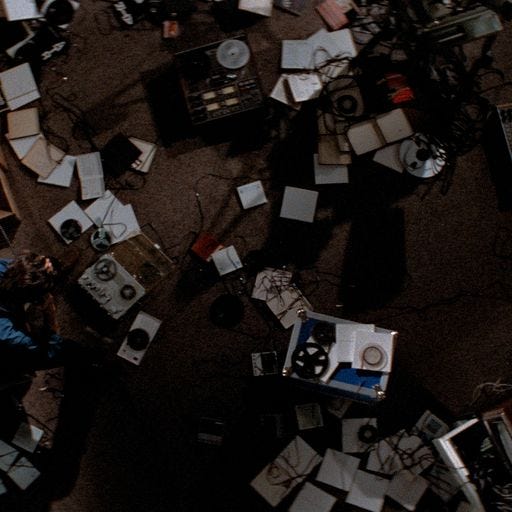

Shadows and Dreams: You have that wistful moment in your book, talking about the Moviola sequence, and how the way you worked for the first 25 years of your career are gone. What do you miss that most about that more artisanal way of making movies?

Paul Hirsch: To be clear, I didn't use the Moviola terribly much. I moved to flatbeds early on, on Sisters. But I did cut celluloid for those 25 years. Doing that required certain skills that are no longer necessary on computers.

I always liked working with my hands, and while we were cutting the movie, we were also creating an artifact, the workprint. It was to be the guide for the negative cutter on how to assemble the final cut, as well as the print we would screen for preview audiences.

The dailies were struck from the original negative and had the best picture quality you could get in those days. The film itself, as it came from the lab, was lustrous and pristine. There was a sensuous pleasure in that. Later, after months of splicing and re-splicing, it could get badly beat-up. If you extended a shot, the splice to the added frames bumped you very slightly, so I tried to avoid that as much as possible.

So there was pride in creating a clean workprint as well as a good cut of the film. It took skill to know precisely which frame to cut on. On computers, you can fool around endlessly, adding or subtracting frames, playing with the cut forever with no consequence. Obviously this is an advantage, but it means anyone can do it, as opposed to needing to possess an arcane skill. I also miss the transformation of time into something concrete that you could control.

That was the genius of film. It gave us a medium through which we could shape time down to a 24th of a second, and preserve those choices forever, or at least as long as the film is preserved.

Shadows and Dreams: The Criterion 4K of Blow Out is stunning. For me the film is a masterpiece, and DePalma’s greatest film. Where does it stand with you?

Paul Hirsch: I'm very proud of it. I've worked with some of the greatest DPs in the history of film, Sven Nykvist, Stephen Burum, Carlo Di Palma, Pawel Edelman, Robert Elswit and many others, but I consider Vilmos Zsigmond the greatest of them.

I expressed my reservations about the picture in my book, but I think when I wrote that, I was over-focusing on the difficulties we faced in reaching the final cut and ignoring the picture's strong points. I love that we inadvertently memorialized an editing process that is now obsolete.

The train station scene with Lithgow is brilliant, although creepy. As for which of Brian's movies I like best, that's impossible for me to answer. It's like asking which of my grandchildren is my favorite.